In my opinion, the best "story" strip of the past 50 years was unquestionably Leonard Starr's On Stage, which ran from 1957 to 1979. At its height in the 1960s, On Stage was unsurpassed by any other strip in its genre, including Alex Raymond's Rip Kirby , Milton Caniff's Steve Canyon, and Hal Foster's epic Prince Valiant. Starr combined a full range of talents to produce On Stage: his drawings sparkled with his fine brushwork and his compelling use of blacks; he captured subtle facial expressions that went beyond anything his peers were doing; he employed strong compositions, his pictures were dramatically and intelligently staged, and he sure knew his anatomy. Above all Starr wrote like a dream; thoughtful, witty and as erudite as his comic page audience would permit. Starr bound all these components together into a consolidated work product that set a new standard for the genre.

John Updike once noted that writers and artists share a common urge to put black marks on paper. Nowhere is the connection between the literary and graphic arts more evident than in comics, where the words climb right into the picture to create a hybrid art form. The creators of comics try to straddle the dividing line between words and pictures, but usually either the pictures or the words dominate. The lesser of the two talents then detracts from the total effect. The medium has a long history of mismatches. There are comics where brilliant drawings are linked to puerile content (such as Alex Raymond's Flash Gordon) or where thoughtful and intelligent stories are saddled with crude drawings (such as Frank Miller's Daredevil). Establishing a balance is difficult, and rare.

Starr was an artist who achieved that balance. His stories, and particularly his depiction of relationships, had insight and depth. The medium has never known a smarter author.

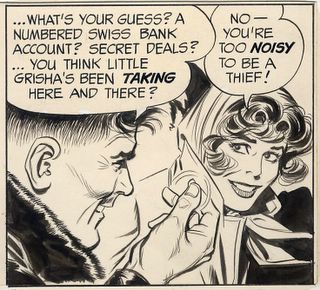

The relationships in On Stage were complex and mature. They made most previous comic strip relationships seem one dimensional and simple minded by comparison.

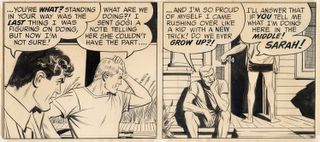

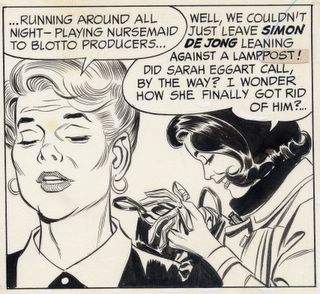

The dialogue in On Stage often contained the humor and irony one might find in excellent fiction.

In addition to thoughtful dialogue, Starr could stage action sequences with the best. (These are, after all, comic strips).

On Stage combined action with wonderful verbal exchanges

Whether the scene was a windswept mountaintop in some exotic location or in a Manhattan foyer, Starr combined dialogue, facial expressions and hand gestures to give On Stage a quality that none of his peers could match.

Starr's crisp drawing style is supported by his understanding of anatomy and design

Starr's Vietnam story was a highpoint of the strip

The poignant end of the visit to Vietnam

The strip went through different phases. Starr originally planned a career as an ilustrator, but anticipating the demise of illustration in the 1950s, he turned to a syndicated comic strip instead. He rode the decline of the story strip until 1979. As newspaper space shrunk and newspaper circulation dwindled, On Stage shed some of its detail and charm, and Starr jumped ship to take over Annie, the successor strip to Harold Gray's Little Orphan Annie.