For most of the 20th century, the primary gripe against illustration was its simple-minded content. No matter how talented or skillful the artist, illustrations for silly romantic fiction in women's magazines or childish advertising slogans just could not be taken seriously.

How odd, then, that in recent years this situation has completely reversed: we have changed from sophisticated illustrations of cartoonish subjects to cartoonish illustrations of sophisticated subjects. Illustrators now deal with the most adult and graphic content, but do so using simple, child-like forms.

Art Spiegelman's crudely drawn comics of talking mice confronting torture and genocide in Nazi death camps won Spiegelman a pulitzer prize.

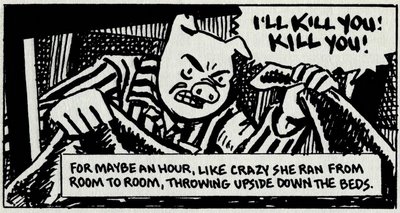

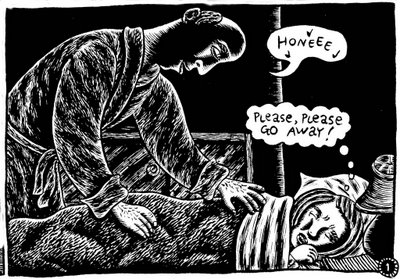

Child-like pictures by Debbie Drechsler convey blood curdling stories of incest and molestation.

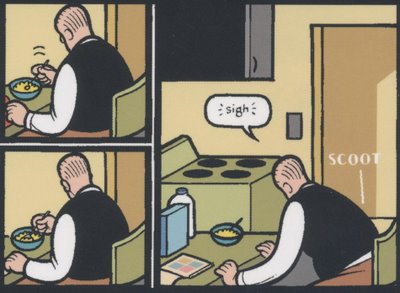

Chris Ware portrays bleakness and alienation using simplistic diagrams reminiscent of industrial instruction manuals.

This trend is evident from the changing mix of artwork in the annuals of the Society of Illustrators. It can also be seen in the work of the "new illustrators" group, the "concept art" crowd and the innovators behind "Raw." What is happening here? Why have form and content switched places in modern illustration? And what does that say about the evolution of our society?

I suspect that there are multiple forces at work. Clearly, illustration lost much of its ambition for technical skill as it fled from the path of the camera. There was not much point in investing years of rigor and discipline to develop skills if illustrators (and the publications that sustained them) were destined to lose the battle to television and photography anyway.

It also seems pretty clear that many of today's innovators didn't want to compete on the home turf of the great illustrators who preceded them. Seymour Chwast confessed that he stays away from techniques and media “that require craftsmanship and a drawing ability I do not have.” Elwood Smith, another highly regarded "cartoon-style" illustrator, recounts that when he tried to draw like the twentieth century “old master” artists with pen and ink, he simply couldn’t do it. But, he says, his inability to render the picture in his mind leads to greater innovation: “if I can’t draw it, I struggle to come up with a different idea that’s invariably more original.” The same could be said of a number of other contemporary illustrators who have shifted the direction of modern illustration.

But there are other, more legitimate reasons for the transformation to child-like styles. Recently, it seems that audiences and creators have become so saturated with mature content that they have become virtually shock proof. It is hard to envision a single vice that has not received ample, repeated and graphic airing. Perhaps for that reason, artists reach for simple, child-like images to reach audiences at a more susceptible and vulnerable level.

The great Mark Twain found that he could create a fresh perspective on adult corruption, greed and slavery by describing them through the eyes of an innocent young boy, Huckleberry Finn. Ever since then, artists have made creative use of the contrast between adult and child-like in various combinations. In the 1950s, Charles Schulz revolutionized the comic strip by putting adult wisdom in the mouths of simply drawn little children. Mel Lazarus used a similar approach with the beautifully drawn Miss Peach.

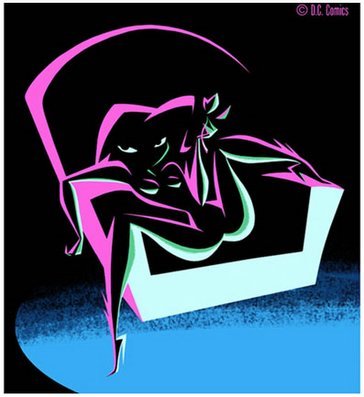

One interesting example of this trend is the use of a simple and innocent 1950s visual style from Disney animated movies and Golden Books to convey a more wicked subject matter. This juxtaposition of form and content can evoke surprising reactions. One of the very best at this is Shane Glines, a creative and prolific young artist with an excellent design sense.

Another such artist is Dean Yeagle. These two, along with other illustrators, seem to be mixing spicy content with innocent images in creative ways. I enjoy their work.

There is of course a larger issue that I have not addressed yet: why do illustrations with mature content but mediocre drawing merit museum shows, laudatory reviews in the New Yorker and pulitzer prizes, while illustrations with simplistic content and superb drawing are chronically snubbed? For example, comic strips like Flash Gordon by Alex Raymond (which had brilliant drawings of goofy stories) will never be accorded the respect that comic strips like Maus or Jimmy Corrigan (which have unimpressive drawings of serious stories) receive. As you might imagine, I have some thoughts on this too, but I have blathered on far too long for one day.