Artists such as Cezanne, Van Gogh, Degas, Gauguin, Toulouse Lautrec and Eakins enthusiastically used photographs as a starting point for their work.

They openly enjoyed the exciting new medium. But illustrators-- nursing a giant inferiority complex-- remained concerned that using photographs might somehow be cheating.

Norman Rockwell recounted his shame when he began to use photographs:

At a dinner at the Society of Illustrators, William Oberhardt, a fellow illustrator, grabbed my arm and said bitterly., "I hear you've gone over to the enemy." "Hunh?" I said, faking ignorance because I realized right way what he was referring to and was ashamed of it. "You're using photographs," he said accusingly. "Oh...well... you know...not actually," I mumbled. "You are ," he said. "Yes" I admitted, feeling trapped, "I am." "Judas!" he said, "Damned photographer!" and he walked away.More than a century later, commenters to this blog hotly debate whether Norman Rockwell's use of photographs undermined his artistic legacy.

Fine artists never felt compelled to justify their methods. Illustrators on the other hand, remained defensive. As a result, the most thoughtful, self-conscious analyses about the use of photography in art tend to come from the field of illustration rather than gallery painting. One of the more articulate artists on this subject was the talented Austin Briggs, who used reference photographs early in his career but soon discovered the limitations of photographs as a tool for quality art:

It was only as I discovered that I did not really possess an image of the object I desired when I took a snapshot that I relegated the camera to its proper place: that of a gatherer of information which has not yet been digested. Only when I reverted to the laborious task of drawing the object directly did it begin to reveal its hidden forms.

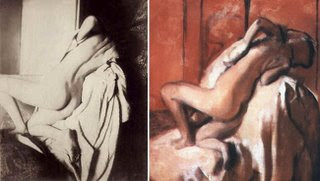

Briggs' splendid drawings made from photographs clearly showed how he digested data and probed for the hidden forms.

Photographs provide an undeniable head start by translating three dimensions into two dimensions for the artist. Nevertheless, Briggs described how artists still need to make important choices in order to distill information from a photograph and find the hidden forms most meaningful to the artist. The glory of drawing is that it is a limited medium; it cannot mechanically capture all data the way a snapshot does, or reproduce a snapshot, and still be successful.

It is also well to remember what [drawing] is not. It is not tone, value or color, although some semblance of all these qualities may be obtained by the sophisticated use of line. Line (drawing in its most straight-forward meaning) is the most limited medium, being solely a matter of measure. It is long or short, angularly obtuse or acute and subject to measure. Measure is the characteristic of line... and line is drawing.

It's necessary to know the limitation one is dealing with in order to use its positive qualities to its fullest advantage. To draw an oak leaf is "an exorcism of disorder" Without knowing what a line cannot do we'd try to express the whole leaf with it, but once we know what a line cannot do, we are on our way toward expressing the leaf in the marvelously simple way a line can function. We begin to to look for the object's anatomy, its real shape reveals itself to us because we must speak with such limited means.

Thumbnail sketch by Briggs captures the essence of the forms

Note how Briggs digested information from photographs in this award winning series for TV Guide.

It does not bother me if a drawing starts from photographs as long as the artist exercises his or her judgment and taste in reducing the photograph into a line medium. That is the part of the artist's job that most interests me.